-

Examples Of SMART Goals For Depression

SMART Goal definition and use in depression

SMART goals, as an acronym, stands for goals that are: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time Bound.

If interested, here’s a post that goes into further details about what a SMART goals is and how to create SMART goals.

In therapy, SMART goals are often used for people with depression (Cheung et al., 2015). When we are depressed, most goals can seem like mountains to climb, which makes us want to withdraw even further inside.

Therefore, setting SMART goals that feel within reach are important to help patients take the necessary steps to get them to where they want to be. It helps to build momentum to break out of the vicious cycle that characterizes depression and inactivity.

SMART goals help us specify general goals

SMART goals help people move towards their overall goals that require some specificity to accomplish.

A few broader goals that one might see in depression are

- Having a stronger social circle

- Becoming more active

- Doing more things that are personally enjoyable

- Keeping to a more regular routine

- Adding healthier and positive activities during the day

Examples of SMART goals to support main goals

Below are several examples of SMART goals that you can use to adapt to fit your needs.

Social circle

- Call up a friend and ask them to have a weekend brunch

- Start a conversation with three people at work this week

- Attend one school social event in the next month

- Try out a new restaurant with husband twice a week

Activity

- Take a walk for 10 minutes in the evening 3 times a week

- Engage in a yoga practice found on YouTube in the morning

- Go for a swim with a friend that enjoys swimming

Personal enjoyment

- Read a book for 15 minutes before bed every night

- Ask partner to take child for an outing and take a hot bubble bath once every few weeks

- Start the day with a cup of chamomile tea

Routine

- Set an evening routine 20 minutes before bed

- Set up an alarm and wake up at 7:15am every day

Healthy activities

- Drink a glass of water upon awakening in the morning

- Cook a healthy meal at least once a day instead of eating out

- Journal for 5 minutes before bed every night

To learn more, here’s a post on scheduling activities in your daily life!

Tips to support SMART goal success

Although SMART goals can sound great and people may initially be motivated to start, there may be barriers that come up to dash our best laid plans.

Therefore, it’s important to consider barriers in order to set yourself up for success by problem-solving ahead of time! A few examples that you can draw from:

- Waking up at 7:00am with an alarm sounds great, but it may be hard to get yourself to get up in that moment when you are feeling tired and cozy. Solution: Tie getting up with something enjoyable, like going to get your favorite Starbucks drink.

- Going for a walk would be lovely, but inertia might tell you stay inside. Solution: Put your shoes next to you and put them on 5 minutes before the scheduled walk. By thinking solely on simply putting on your shoes, this will generate the momentum needed to get out the door!

- Wanting to do something you enjoy for yourself, but you have a baby to take care of, which limits your time. Solution: Ask your partner to spend 15 minutes with the baby in the evening so you have some alone time to do something you enjoy.

- Setting up plans with your friend but they don’t pick up or can’t make the lunch. Solution: Have another friend in mind that you can call if the other person cannot make it.

Beyond troubleshooting, it is important to start small and scale up. For example, if 30 minutes of reading sounds pretty daunting, consider 15 minutes, 5 minutes, or even just one page (reading more if you want). The important part is to set yourself up for success!

If interested, here’s a YouTube video I made on the same topic in further detail!

Best wishes,

P

-

6 Ways To Avoid Burnout In Graduate School

The 6 year marathon

The saying goes, “graduate school is a marathon, not a sprint”.

This saying is intended to reduce rates of burnout in graduate students. However, this saying forgets that a 26.2 mile run (or in this case, a 6 year program) can still be incredibly tiring in its own right.

Student burnout is extremely common in PhD programs of clinical psychology. One study found that 60% of doctoral students in clinical psychology experienced significant burnout with little direct training on how to handle stress (Zemirah, 2000).

Throughout my graduate career, I have found a few strategies to be helpful for myself to reduce burnout. For those experiencing burnout/have experienced burnout, I would encourage you to keep reading to see if any of these suggestions resonate well with you to try out in your own life!

#1 Focus on what’s important to you

Most students in graduate school tend to be overachieving and perfectionistic – that’s what got them the grades and accolades to get into grad school in the first place. However, this trait can backfire in grad school when there is no shortage of readings and work to do.

In graduate school, many of my mentors have stressed that “good is good enough”. Do reasonably well in your classes, but do not strive for perfection.

In my classes, there were many students who would spend hours upon hours ensuring that their reflection papers and presentations were done to complete perfection. This approach to work led to a significant amount of distress and was a one-way ticket to burnout.

In my graduate studies, I did my best to calibrate the amount of work needed to perform reasonably well, and was able to focus my time on activities I really wanted to pursue in graduate school.

For example, I was able to travel to attend conferences, conduct guest lectures, and engage in university affairs in my first-year, which is known at my program to be typically dominated by coursework. At the expense of a few A+ grades, I had a lot more time on my hands for myself and was able to do things that I was passionate about.

When you enjoy the work you do, burnout becomes less likely. In the same vein, be choosey in deciding which additional responsibilities to take on and ensure that they are things you enjoy or will have a positive impact in your future vocational career.

#2 Do the good things for your health even when it’s hard

As trite as it sounds, it is truly important to take time out of your day to engage in practices that are beneficial for your health. For example, I try to take some time every day to exercise, engage in a mindful meditation, and practice gratitude. The latter two activities take no more than 10 to 15 minutes (and can be shorter if you wish – some mindfulness practices are only a few minutes).

Some individuals may counter this by saying that they do not have enough time to engage in these types of activities. Personally, I would argue that engagement in these activities paradoxically leads to more time – both in terms of work efficiency and time to enjoy the rest of your day.

The Pareto principle (known as the 80/20 rule) states that 80% of work is completed in 20% of time. Activities like meditation and exercise can be helpful in increasing concentration for deep work to be conducted, rather than switching between work, TikTok, messenger, Netflix, and Reddit for 12 hours. Moreover, these activities nourish you with added resources that can be helpful for work and beyond.

Even if it can be tough, I would encourage you to experiment adding a few nourishing activities in your life (starting with a few minutes a day) to see the benefit it has on burnout. Atomic Habits by James Clear can be a very helpful resource to setting healthy habits.

The PLEASE skill is a set of emotion regulation skills that can also be helpful to learn about behaviours that are helpful to nourishing ourselves to feel less emotionally vulnerable, which could be a pathway towards reducing burnout.

#3 Have a strong social support network

Graduate school, especially in clinical psychology, tends to have a small close-knit cohort because the training model only allows for a limited number of spots in each year (~somewhere between 5 to 10 new students).

Therefore, you tend to develop strong friendships with people who are going through the same journey as you and are able to empathize and validate your experience. Being open and vulnerable with these individuals can be a great way to reduce isolation and strengthen your social circle.

Beyond students in the program, I would encourage you to stay in contact with family members, friends outside of the program, and other loved ones. Make sure to keep some time for these people in your life – set up a brunch with a friend; call your mom once in a while (if you two are on agreeable terms). These types of interactions can ensure that grad school does not completely envelop your life.

Another graduate student described grad school as a gas that takes up as much room as you allow it. I agree with this statement.

#4 Engage in enjoyable self-care activities

One of the best things about graduate school that I have found is the flexibility it confers. Although long hours can be common, many of the activities of graduate school (e.g., assignments, readings, writing manuscripts/research grants, etc.) tend to be done at your own pace. Depending on your program, scheduled hours (courses, clinical work, meetings, etc.) probably do not take up more than 15 to 25 hours of your week.

Personally, I take advantage of this to be able to enjoy parts of my day during the typical 9 to 5 hustle bustle – I go try out restaurants, take a walk in the park, sleep in once in a while, and go to the gym as examples of self-care. Other examples include:

- Reading a novel for fun

- Watching a movie

- Taking a warm bath

- Planning a get away with a friend or a romantic partner

- Cozying up and watching a fun show

Taking advantage of this flexibility also means I also work in the evenings and weekends, but it’s a freeing schedule that works well for me because I try to be efficient with my work time and do not second guess the quality of my work. Other students prefer to keep to a strict 9 to 5 and have evenings and most weekends to themselves for destressing – that works too. I would encourage you to reflect and determine which strategy works best for you!

#5 Give yourself a pat on the back

Sometimes, we’re so busy second guessing ourselves and feeling overwhelmed, that we forget that we have done a lot a good work with the students we mentor, the patients we see, or the people we collaborate with.

Consider times in the past where you might deserve a pat on the back. Perhaps a grateful patient that you have recently finished up with and have seen some really improved outcomes throughout session. Or a student who felt a lot more confident about their paper after speaking with you in an office hour session. Even some strong feedback from a supervisor or another professor about your research idea. Take a moment to know that you are incredible just by virtue of being in graduate school and working hard to move towards your goals.

We’re all living the dream – at least in someone’s eyes.

#6 Engage in counselling or therapy

Many of us in clinical psychology provide counselling and psychotherapy, but may never have had experienced it on the other side of the table. Given the increased rates of anxiety and depression in graduate students (Garcia-Williams et al., 2014), we may be a specific demographic that requires it the most!

It’s definitely encouraged to try out counselling at least once in your life to see if it has benefits for you. Moreover, understanding therapy from the patient’s perspective can be useful to improving your own clinical awareness.

If you found this post helpful, please consider subscribing to the mailing list!

Best wishes,

P

References

Garcia-Williams, A. G., Moffitt, L., & Kaslow, N. J. (2014). Mental health and suicidal behavior among graduate students. Academic psychiatry, 38(5), 554-560.

Zemirah, N. L. (2000). Burnout and clinical psychology graduate students: A qualitative study of students’ experiences and perceptions. Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

-

How To Lead Mindfulness Practice As A Therapist

Mindfulness in therapy

Mindfulness has become increasingly popular as a third wave therapy in psychological treatment.

Unlike traditional cognitive therapy, which emphasizes more on changing negative thoughts that maintain our mental difficulties, mindfulness practice focuses on acceptance of our thoughts.

It is based on the idea that what we resist, persists. The more try to run away from our anxiety, the stronger anxiety gets. The more we try to sleep, the further away sleep gets. By simply observing our negative thoughts non-judgmentally – i.e., not giving it emotional fuel or believing in it – the power of the thought decreases dramatically and we become better able to act in a way that is consistent with our values. In the same vein, when we accept the fact that sleep might never come, that is when sleep finally comes.

Meta-analytic studies have found that mindfulness is helpful across a number of psychological and medical conditions, such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, emotion regulation, chronic pain, among many other disorders (Khoury et al., 2013).

Mindfulness is incredibly helpful. However, learning mindfulness can be somewhat challenging because it requires us to adopt a new way of relating to our thoughts and emotions. Many people practice mindfulness for the wrong intention, thinking to it is meant to relax us.

However, mindfulness is not relaxation. Assuming that all mindfulness practices will be positive experiences can lead to people terminating early because they think that mindfulness is not working.

Therefore, it is vital that therapists understand how to engage and lead mindfulness practices with patients in individual and group therapy to transition patients into a new way of thinking and practice that can be widely beneficial.

The goals of mindfulness

Firstly, to understand how to lead practices, it is important to understand the goals of mindfulness. Three goals of mindfulness include:

- Attending to the present moment and noticing internal (thoughts, emotions) and external (sounds, tastes, touch) sensations.

- To accept the current experience as it is and taking a non-judgmental approach to internal and external events

- To get out of one’s automatic pilot to better respond to emotions, rather than react emotionally

As you can see, mindfulness is about seeing thoughts and emotions as they truly are – simply thoughts and emotions. They do not have to mean anything and we do not have to react to it. By attending to the present moment, we become better aware of how our thoughts and emotions and affect our behaviours and make a decision to respond instead of immediately reacting.

For example, our automatic pilot may have previously taken us to using substances anytime we are anxious. Through regular mindfulness practice, we may become much more aware of these behaviours and choose to adopt healthier habits to reduce stress – such as regular relaxation exercises or increasing emotional vulnerability.

Embodying attitudes of mindful practice

Mindfulness is an elusive concept and can be best understood experientially. Therefore, to be fully effective in teaching mindfulness means that it is important to practice mindfulness. I would encourage you to set aside some time every day to try out mindfulness practices for yourself. For those pressed for time, there are practices that are as short as 3 minutes!

Beyond personal practice, it is also helpful to adopt an attitude of embodied mindfulness to work with patients in a way that consistent with the teachings of mindfulness. A few examples below:

A non-judgmental attitude. After a mindfulness practice, we typically ask patients to share their experience. During this time, we adopt a curious and non-judgmental attitude towards their experience. We are simply interested in hearing what their experience was regardless of whether it was positive or negative. This embodiment of a non-judgmental attitude allows others to understand that it’s okay – and even good – to have bad experiences and be more open to sharing. The reason that bad experiences are useful is because they allow us to practice our ability to simply observe, acknowledge, and dismiss negative thoughts or sensations.

Adopting a beginner’s mind. Although we may be leading the mindfulness practice, it is important to take a beginner’s mind to each mindfulness practice and the patient’s respective experiences. If we are fixed in our beliefs, then we may miss essential components because of our limited worldview. By adopting a beginner’s mind, we are much more open and curious about the patient’s experiences.

Being kind. We show compassion to our patients’ and our own experience and provide copious empathy to each person’s journey. Showing genuine positive regard increases trust and is a key component of Carl Roger’s humanistic psychology.

Non-striving and letting go. We are not forcing anything to happen or trying to make patient’s change their minds about anything. In this practice, we let go of wants, needs, wishes, to simply notice what is going on in our experience, making note of their existence, and then letting them go.

This post can be helpful to learn more about specific attitudes of mindfulness.

Layers of mindfulness inquiry

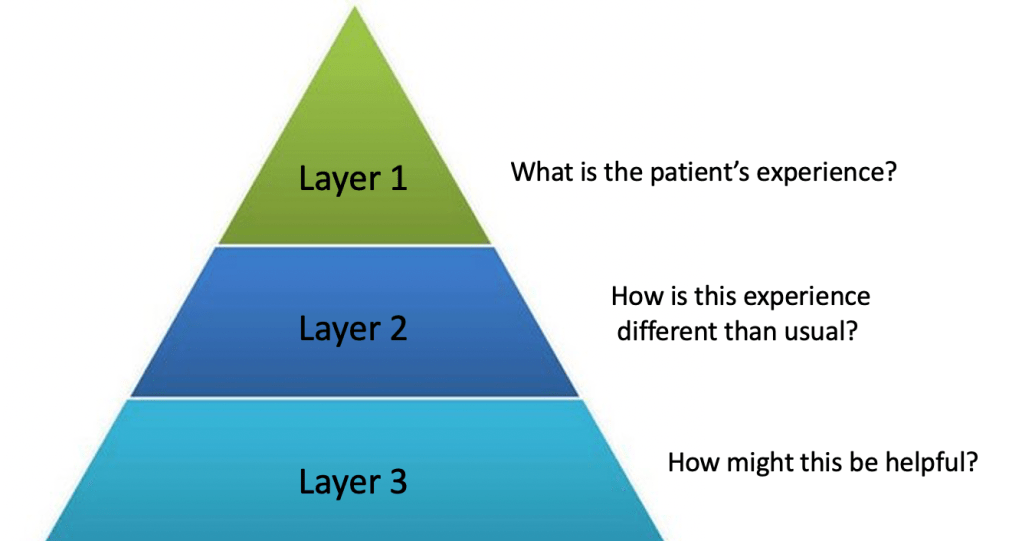

The structure of mindfulness practice in group therapy is that a therapist will typically lead a mindfulness meditation or mindfulness practice. Afterwards, each patient will have a chance to share their experience. The specific questions that the therapists asked are based on a specific structure (known as ‘layers of inquiry’) that help guide our questioning to support a mindfulness approach.

Layer 1: In layer one, the teacher attempts to understand a person’s experience, acknowledging its presence and allowing space for it. Example questions include: “What did you notice?”, “What were you aware of?”, and “What showed up for you?”. Many experiences can come up, but you may hear things like: “I noticed my mind kept going off into different places”, “I felt a lot of anxiety in my chest”, and “I was feeling very calm and focused”. In none of these cases the patients are doing something wrong – we take a non-judgmentally attitude towards all experiences!

Layer 2: Layer 2 focuses on expanding this awareness to the sensations and how it relates to their current habits or behaviours. For example, a question could include “how might this be different than when you normally pay attention?”. The patient may have insight into how these sensations typically increase urge to engage in certain behaviours or notice that simply observing their anxious sensations actually helped them to focus their breath on the anxiety.

Layer 3: Layer 3 is about understanding how this break from the automatic pilot helps us with our mental health. From noticing these thoughts and sensations and recognizing associated urges to engage in certain behaviours, how we do use that to increase well-being? Perhaps, for some, noticing and holding these thoughts non-judgmentally weakened their strength and made them feel more in control of their subsequent behaviours. In other cases, understanding that a thought is just a thought – and labelling it as such – helped to reduce their distress. Layer 3 asks questions about how mindfulness might be helpful in improving their psychological challenges.

An example of mindfulness inquiry after practice

Therapist: So Sarah, what was the experience like for you? What did you notice? (Layer 1)

Patient: I noticed my mind was running back and forth about all the things I had to do after today’s session. I feel like I didn’t do a good job.

Therapist: So you noticed that your mind was jumping around a lot and you had a judgment that “you were not doing a good job”, is that right?

Patient: Yes, that’s right. I feel like I should have been able to focus better.

Therapist: Yes, I think we can all agree that we have times in our lives that our brain sends a bunch of signals about things we need to worry about and we notice it’s hard to focus on the task at hand. That’s just what the brain does! And mindfulness is really about noticing that our mind is running, even thanking the mind for doing what it does, and then going back to our practice. What about you Sarah – did you notice anything different when your mind was running compared to usual?

Patient: Yeah, I noticed I was frustrated when my mind kept going to all the appointments and tasks I had to attend to. But, I just tried to get back to focusing on the breath. I noticed by the end of the practice I was able to keep my concentration a lot better.

Therapist: Wonderful! I’m glad to hear that Sarah. And how do you think this practice might benefit you in the future.

Patient: For me, I think this practice is helpful for me to not get so frustrated when I am having a lot going on. I can always go back to the breath, which gives me more space to think about what I need to do first instead of just getting overwhelmed.

Final thoughts

And that’s it! Leading mindfulness practice is really about helping patients experience things going in their lives in a non-judgmental and present manner. This gives them the space to respond according to their own goals and values and not give negative thoughts and emotions the fuel to hurt us. Adopting a specific set of attitudes, using the layers of inquiry, and practicing mindfulness yourself can help you to become an excellent mindfulness therapist!

If you found this post helpful, please consider subscribing to the mailing list for more evidence-based information on mental health!

Best wishes,

P

-

6 Ways Therapists Should View Their Patients For Better Outcomes

The patient is active, not passive

In therapy, the patient is not a passive being that the clinician works on or something broken waiting to be fixed – like a car at the mechanic.

They are autonomous individuals capable of their own thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Therefore, the therapist and patient must enter into a collaborative relationship and work together to break negative cycles maintaining the patient’s problem and get them closer to their goals.

Unsurprisingly then, the therapeutic alliance, the relationship between the healthcare provider and the patent, is an incredibly important component of therapy. The therapeutic relationship provides a safe and trusting space to mutual work towards a shared goal.

Positive working relationships are found to improve treatment outcomes in virtually every disorder (Horvath & Symonds, 1991). To support a positive and equal working relationship, there are certain ways that therapists should view patients to support a strong and equal working alliance.

#1 Patients are inherently good

Even for the most patient of saints, there will be times that you will be annoyed or frustrated with your patient. For example, if they consistently don’t complete their home practice or if they disclose something having engaged in violent or disagreeable behaviours in their past that may be particularly sensitive to your own values.

Despite these instances, it is important to remind yourself that the patient you are working with has strengths and positive qualities of their own.

Try to focus on positive qualities of this individual. Perhaps they are always on time for their appointments. Maybe they are insightful about their struggles and grasp the material you provide well. Or they appear to be a very strong and caring parent to their children.

Pick something out and remember that. It is hard to be kind and compassionate to someone you do not believe is good or worthwhile. Carl Rogers, a founding figure in Humanistic psychology, believes that people are inherently good and simply need empathy and unconditional positive regard to become their best selves. This means trying to see things from the patient’s perspective and considering them a good person even if you do not agree with certain actions.

Fortunately, all patients I have worked with have had strengths and positive qualities – some of which became much more noticeable the more I positively worked with these individuals. It is also important to reinforce patients of these characteristics when talking to them.

#2 Patients have their own goals and values

It is important to remember that your patient has their own goals for treatment. You may notice other ‘problems’ to be solved or obvious goals if you were in the patient’s situation, but you should always focus on the specific needs of the patient.

Each person has distinct values – things that they find most important in their lives. As therapists, we can share our concerns and dilemmas; however, we should not impose our own values on the patient in terms of what they want in treatment.

For example, you might share your concern that the patient’s goals could lead to other issues, or that the treatment would not be a good fit for their goals. In this case, the patient may decide to work differently with you or you can work together to search for another clinician that can provide the treatment they are looking for.

Focus on where the patient is currently at and prioritize their needs in treatment over your own. One exception is if the patient is

#3 Patients are unique in what strategies work well for them

What works well for one patient may not work well for another. Therefore, therapists must be flexible and considerate about what might be most helpful for each unique patient.

For example, some patients may prefer to work cognitively on their negative thoughts, which may warrant the use of thought records.

On the other hand, other patients may find more utility in behavioural strategies, such as behavioural experiments or mindfulness strategies.

Use your clinical observations to inform how you think about the case and be willing to experiment with different strategies with your patient to see which one works best for them!

#4 Patients are shaped by past experiences

Past experiences can affect how patients view themselves, others, and the world. For example, if their parents were generally uncaring to them when they were young, they may be suspicious of why you are being kind to them and wonder whether you have underlying motives for being so nice.

Understanding how the patient’s past experiences affect their present cognitions and behaviours can be instrumental provides insight into what might be maintaining a patient’s problems. This insight also allows you to share how certain strategies might have been helpful in the past (e.g., being aggressive to get what you want) but may be problematic in their present life.

#5 Patients want to change

Although it may not feel like it sometimes when patients are pushing back against your every word and haven’t done their home practice for the third week in a row, patients are not intentionally being difficult and do want to change. That’s why they are in therapy.

However, there may be barriers or conflicts that make change difficult. For example, they may want to develop a stronger social circle but be paralyzed by fears of negative evaluation from their peers and deal with struggles of worthlessness. They may also be worried that the change in lifestyle may affect their ability to have alone time – something they also value.

All these components make the task of being more social a lot more difficult to approach. It is your job to unpack these challenges and work with the patient to help them decide what is best for their lives. This may be troubleshooting more practical errors, such as deciding who the patient should call up to spend more time with, or targeting cognitive beliefs about self-esteem or black and white thinking about having to choose between friends and alone time.

#6 Patients have different definitions of success

What the therapist thinks treatment success may not be the patient’s perception of success. For example, clinicians may want the patient to fully abstain from substance use, but the patient’s own goal may be to reduce their use but not eliminate it completely.

Although we may have well-intended reasons to have a different goal, it is imperative to follow the patient’s decision and not impose our own values onto them. Again, we can share our thoughts, but the choice should ultimately come from them. It is hard to follow through when something does not come from ourselves. Determine what the patient’s goal is and work with them to get them to where they want to be.

Summary

The therapeutic alliance is one of – if not the most – important factors for positive treatment outcome. At the very least, patients will have a positive experience working with you and be more likely to come back to treatment in the future. Hopefully, learning a bit about these components to a strong working alliance has been helpful

Please consider subscribing to the mailing if this post was helpful!

Best wishes,

P

-

Daily Activities Of A Clinical Psychology PhD Student

Introduction

For people interested in pursuing a degree in clinical psychology, they may be interested in learning about the typical activities that a graduate student gets up to on a day to day.

As a clinical psychology student myself, I find the daily life of a clinical psychology student to be exciting and varied. No two days look exactly the same and days are formed by a mishmash of different tasks and activities that are personally enjoyable and meaningful.

Moreover, the flexibility of schedule can bring you out of the city for interesting research/learning events or allow you to enjoy activities that a normal 9 to 5 may not permit. For example, going to the gym on a Thursday morning or checking out a new restaurant on a Friday afternoon.

As long as you stay on top of your work, this schedule can be quite freeing (though you might have to do some occasional work in the evenings/weekends). Personally, I am willing to make that trade-off, though I am aware it is not for everyone.

In this article, I provide an example of some of the activities you might engage in as a PhD student in clinical psychology and provide a couple examples of a daily schedule as a student in this profession.

Coursework and continued education

Unsurprisingly, classwork is a significant part of graduate education. However, the amount is less than what you might expect of a full courseload in undergraduate studies.

Typically, PhD students take around 2 courses per semester with some academic semesters being less intensive in terms of coursework to focus more on research or clinical work. For example, I took 3 courses in my first couple semesters of my Master’s, but there have been semesters in my PhD where I did not take coursework because there were no electives that were of interest, and I wanted to focus on other areas of my degree like my dissertation.

Courses are centered around research methods/statistics, ethics, assessment and treatment of psychological disorders, along with other psychology electives (e.g., developmental, neuroscience, forensic psychology, etc.). Typically, students have classes a couple days of the week with lectures being 3-hours long.

Beyond coursework, there are many opportunities to further your education through clinical rounds, invited speaker talks, and workshops that a student may attend.

Clinical work

Many students provide assessment and treatment to patients in different clinical contexts: clinical practica, clinical research, and/or private practice. These training opportunities are built-in to the program degree.

Depending on the time of year, students may see 4 to 5 patients a week for assessment, individual therapy, or group therapy. Students are trained in conducting structured interviews, providing evidence-based therapies (for example, cognitive behavioural therapy), and receive supervision from licensed psychologists.

Consequently, studying up on clinical techniques, preparing for patients, seeing patients, and writing clinical/assessment notes play a significant role in terms of daily activities.

Research

Research is an integral part of a PhD clinical psychology program. Examples include: conducting literature reviews; collecting and analyzing data; working with participants; writing manuscripts; grant writing; and presenting results. These tasks may be as part of on-going research projects in the lab or your own thesis/dissertation work.

In our lab, clinical work and research is often combined because we run clinical trials evaluating treatments of insomnia. Therefore, a day may include providing therapy for participants with insomnia and evaluating changes in their insomnia severity scores.

Teaching/marking

Many PhD students are employed in the university as a teaching assistant or course instructor. Therefore, days may also include some form of teaching work – marking exams, conducting lectures, holding office hours, etc.

Holding these positions are also a good way to supplement your income.

Attending conferences

One great way to travel on a limited budget is by attending conferences in other cities and countries. Presenting a poster or speaking at a conference can be a great way to obtain tangible evidence of research productivity, develop connections, and obtain grants to travel.

I typically go to 2 to 3 conferences per years and have visited unfamiliar cities in Canada and the States. Some students also get to travel internationally to other continents, which can be a fantastic experience to do some sightseeing along with learning more about cutting-edge research in your area of interest!

University affairs and other work

Beyond the activities listed above, there are many ways to engage in further work or volunteer opportunities especially at the university. For example, I am working in a consulting position for undergraduate writing and take on several positions at the university – the research ethics board, academic integrity council, and mentorship programs. The specific choice of which and how much involvement you wish to engage in at the university is completely up to your discretion!

An example of a busy day as a PhD student in clinical psychology

You certainly do not do everything every single day – there would never be a moment to relax if you did! Some days can be busier and some days can be a bit lighter depending on your schedule. Here’s an example of a typical (busier) day:

7:00am – Get up, hygiene, and get dressed to go out

8:00am – Respond to daily emails and do some pre-readings prior to class

9:00am – Attend psychopathology class

12:00pm – Lunch and review case files for incoming patient

1:00pm – See patient for intake assessment

2:30pm – Write up patient notes

3:00pm – Meeting with supervisor to discuss dissertation ideas

3:30pm – Work on a critical reflection essay for a course

4:00pm – Hold office hours for students to review exam

5:00pm – Go home, get some R&R, eat

6:30pm – Continue literature review for dissertation and conduct analysis to submit an abstract to a conference

8:30pm – Dinner

9:00pm – Makes notes in preparation for treatment patients the next day

10:00pm – Relax and get ready for bed

**Note. This is a sample of a busier day. Moreover, some students prefer to stick to a strict 9:00am to 5:00pm schedule to ensure a proper work-life balance – so this certainly doesn’t have to look like your schedule if it made you anxious. Personally, I don’t mind a longer day (or a weekend workday) because of the flexibility that less busy days confer.

An example of a less busy work day as a PhD student in clinical psychology

8:00am – Wake up and get ready for the day

9:00am – Go to the gym

10:30am – Attend lab meeting

11:30am – Respond to emails and work on short reflection paper

1:00pm – Go to lunch at a new restaurant

2:30pm – Do some light reading and work at a coffee shop

4:00pm – Supervise an assessment session for a junior colleague

6:00pm – Spend time with a friend and watch a movie

8:30pm – Have dinner

9:00pm – Brainstorm a few ideas for a manuscript

9:30pm – Chill out, watch a Netflix show, and do some light yoga before bed

As you can see, work is still being done but the workload is significantly less and there is substantial flexibility in when you do work and when you want to do things for your own development (gym), enjoyment (checking out a new restaurant or watching a movie with a friend), and personal time (chilling out). Moreover, you are able to engage in these activities at ‘odd-hours’, which can feel quite freeing. There won’t be as many people in the gym during these hours and you likely won’t need a reservation to try out a popular restaurant at 1:00pm on a Wednesday.

Summary

The life of a PhD student in clinical psychology can be varied, dynamic, and freeing depending on how you approach the day.

For some people, it can be quite stressful because they feel like they have to do work all the time – grad school consumes their entire life.

I personally approach graduate school from a more positive and balanced framework – tough, work-filled days feel productive, meaningful, and dynamic; lax days feel freeing and enjoyable (though I try to still do a little work every day to keep ahead of the work curve).

In doing so, I have found a perfect balance that works for me. However, what works for you may not be the same as what works for me. I would encourage you to consider the types of days and specific activities you want to do and curate your schedule based on that!

I hope this post was helpful to learn a little more about what the daily life of a PhD student in clinical psychology looks like!

Please consider subscribing to the mailing list for more useful information in the field of mental health!

Best wishes,

P

-

5 Differences Between PhD and PsyD In Clinical Psychology

There are many career pathways to working with patients in a therapy setting: clinical psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker, nurse practitioner – to name a few.

For those who are interested in registering under the protected term of ‘psychologist’, there are two primary degrees that one can pursue for this career path. These are the PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) and the PsyD (Doctor of Psychology).

People often hear these terms when searching up careers in clinical psychology and may be curious to understand the difference between these two degrees. Below, I provide information on 5 key differences between the PhD and the PsyD to help determine which one you should pursue.

Research Intensive Component

Perhaps the biggest difference between the PhD and the PsyD is the extent of research involvement.

The PhD is a research-intensive program, in which research is a significant part of course work and degree milestone. The student is expected to develop an original research project for their master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation. These components include writing a research proposal in consultation with committee members, submitting research ethics applications, collecting and analyzing data, writing up a comprehensive manuscript, and defending your dissertation.

On the other hand, the PsyD may include courses in research methods but do not require a substantive amount time spent on original research projects.

Consequently, the PhD may provide a more holistic training emphasizing both research and clinical work (scientist-practitioner model); however, PsyD may be more desirable if you do not enjoy research and wish to primarily work with patients in the future.

Clinical Emphasis

Although a PhD has a heavy research component, this does not mean that the program does not rigorously train students in psychological assessment and treatment as well. Many PhD students have intensive course work to develop as a clinician and complete practica at different sites (e.g., hospitals, private practice) to develop into a clinician. Because of the rigour of both research and clinical work, statistics for successful matching to internship applications (which is required to be licensed as a psychologist) is typically higher in PhD compared to PsyD programs.

Funding throughout the program

The PhD program is fully funded because it is a research-intensive program. You get paid to do research and conduct activities at the university, such as teaching assistantships.

Most students can get by through living a modest means depending on the funding structure – though there are ways to increase your income. Although the funding isn’t particularly impressive, it is possible to get through your PhD without incurring significant debt.

On the other hand, you kind of have to pay your way through the PsyD. And the PsyD is expensive – many programs run somewhere between $100,000 to $200,000. In this case, accruing a significant debt is norm rather than the exception.

Because of the costly aspect of the PsyD, this can be quite profitable for certain programs to operate as a windmill for degrees and are interested in your money rather than investing in your education. Because of this, it’s important to do your due diligence and make sure that the program you are entering is legitimate and successful in getting you matched to a strong internship program.

Competitiveness of PhD vs the PsyD programs

Unsurprisingly, a fully funded PhD program is more competitive compared to a PsyD which you must pay through yourself. Admission rates for PhD programs tend to be quite low – somewhere around 5 to 10% whereas PsyD programs can be much higher depending on the specific program. More intensive and rigorous PsyD programs can still be quite competitive. Here’s a guide on determining whether you are a competitive applicant for PhD programs if interested!

Duration of the program

The PsyD program typically takes between 4 to 5 years, whereas the PhD program can take significantly longer (6-7 years). The biggest reason is likely the research component, which requires more time to complete.

Therefore, if time is an important consideration, then a PsyD may be more appropriate. That being said, there are programs, such as social work, that allows you to engage in therapy with patients with significantly less time and cost compared to the PsyD.

Summary

Overall, there are pros and cons of the PhD and PsyD. It is important to take these factors into consideration if you are interested in the career path of a clinical psychologist.

I hope this post was helpful! Please consider subscribing to the mailing list for more information regarding clinical psychology as a degree and a profession.

Best wishes,

P

-

How To Improve Sleep Hygiene For Optimal Sleep Health

What is sleep hygiene?

Sleep hygiene refers to best practices for behaviours and environmental factors that are most conducive to sleep (Stepansky & Wyatt, 2003). Specifically, they are a list of things we can do in our lives to reduce possible disruptions in our sleep and make sure that the environment is a good place to sleep.

Although sleep hygiene may not be the answer to more challenging sleep problems, such as chronic insomnia, proper sleep hygiene can lead to better sleep outcomes (Caia et al., 2018).

Below are some tips to improve sleep hygiene for optimal sleep health.

Improving the sleep environment

Temperature. Temperatures that are too high can make it harder to fall asleep, lead to more awakenings in the middle of the night, and even reduce the amount of time we spend in deep sleep (Okamoto-Mizuno & Mizuno, 2012). On the other hand, cold temperatures can impact our heart rate response which could be related to adverse cardiac events (e.g., heart disease). Therefore, choosing a comfortable temperature can be helpful to keep sleep quality and quantity high.

Noise. Unsurprisingly, loud noises can also be a barrier to falling asleep/staying asleep. Noise cancelling headphones or other strategies to minimize sound during sleep can therefore be helpful. Some people find it useful to listen to white noise or pleasant sounds; in this case, I would encourage you to continue with the things that work well for you and that you enjoy!

Light. Reducing light exposure can help our body set the stage for sleep. If ambient light is a problem, blackout curtains can be a useful investment to optimize the sleep environment.

Mattresses/blankets. A well-chosen mattress, blanket, and pillow can also help with making sleep more conducive. For some, weighted blankets may help to reduce anxiety and stress (Eron et al., 2020). With respect to mattresses, people may have differing preferences for the firmness of the mattresses. Even other components of the sleep environment, such as pillows and pajamas, may be important to consider if the ones you are currently using are causing you grief.

The nighttime routine

Additional Do’s and Don’ts

1. Avoid caffeine in the evening

The half-life of caffeine is about 5 hours. Half-life is how long it takes for 50% of caffeine to be eliminated from your body. Therefore, it is best to avoid consuming additional caffeine after the late-lunch period. Otherwise, the remaining effects of caffeine could be stimulating and affect your ability to fall asleep.

2. Avoid substance use like alcohol and marijuana

Although the antidepressant effects of alcohol and marijuana can make it easier to fall asleep, the chemical breakdown of these drugs can lead to more awakenings in the middle of the night. The result is falling asleep quicker, but less refreshing, troubled sleep overall. Avoid non-prescription drugs especially during the evening for proper sleep health.

3. Limit vigorous physical activities in the evening

Although increasing physical activity during the day can be helpful to increase pressure to sleep (which helps with consolidating sleep and increasing sleep quality), intense physical activity in the evening could increase physiological arousal and make it harder to fall asleep. If you enjoy moving around in the evening, it is recommended to keep to light activities, such as walks and yoga.

4. Avoid eating heavy dinners

Eating a heavy dinner can lead to acid reflux in the middle of the night because you are laying down, which could affect how gravity keeps the food in your stomach. Heavy foods can also cause your metabolism to run faster and send more blood to your brain causing vivid dreams or nightmares.

5. Daily relaxation strategies are helpful

Finally, keeping to regular relaxation practice in the morning or afternoon can be a great way to reduce stress, which can help with sleep. It is recommended to engage in relaxation exercises outside of the bedtime routine because we do not want to create an association between ‘needing to relax’ and falling asleep. Efforts to sleep can sometimes move into more insidious territories of being a crutch for good sleep. Over time, this can lead to insomnia.

Final comments

I hope this post was helpful to learn more about ways to optimize your behaviours and the environment for good sleep hygiene! For those interested, here’s a couple interesting posts on feeling more energized in the morning and goals to set to optimize your sleep!

If you found this post helpful, please consider subscribing to the mailing list!

Best wishes,

P

-

How Long Does It Take To Become A Clinical Psychologist

Introduction

The road to a clinical psychologist is a long one. Folks who are interested in the career may be curious about exactly how long it takes to become a fully autonomous practicing clinician.

The answer is pretty darn long – especially for the traditional PhD route. There are quite a few educational and professional hoops and milestones to jump through to become an independent practicing psychologist. We are thinking on the time scale of years.

In this post, I clarify how long it takes to become a practicing clinician and specific milestones that are required at each stage.

Obtaining your undergraduate degree

Although there are people who begin truly pursuing their clinical psychology career after finishing undergraduate, many begin to consider this path in the beginning or in the midst of their undergraduate studies.

They will likely major in Psychology for their undergraduate degree, join an Honour’s program, take relevant coursework, and conduct extensive research. Although this is the traditional path, you can apply even if you majored in a different program with sufficient relevant coursework and experience.

Clinical psychology PhD programs are very competitive, so early consideration and preparation through a strong academic track record and extensive research experience will be vital to being a competitive applicant. Here is a guide on how to best prepare for clinical psychology programs in your undergrad if you’re interested!

Assuming a typical Bachelor’s degree, the undergrad will take around 4 years. However, it is the norm rather than the exception for some students to take an extra gap year to obtain further research experience and prepare for applications rather than go straight from undergrad to graduate school. So far, we are looking at somewhere between 4 to 5 years.

Obtaining your Master’s degree

The Master’s and PhD program are typically built-in together; that is, the program expects you to complete both as most jurisdictions require a PhD to consider yourself a psychologist.

The Master’s degree is typically 2 years. During this time, you will complete relevant coursework, such as research methods, statistics, in addition to courses on theories on psychopathology (mental disorders), assessments, and treatments. The specific treatment you will specialize in (e.g., cognitive behavioural therapy, humanistic psychology, etc.) depends on the program and its specialized training.

During this time, you will also begin to see your first patients and complete a Master’s thesis as an independent research project supported by your research supervisor.

Obtaining your PhD degree

The PhD is more variable than the Master’s degree in terms of length because people can take more or less time to complete their doctoral dissertation. Usually, the length of the PhD is somewhere between 3 to 5 years.

Besides the hefty doctoral dissertation that you will propose, collect data for, and defend, there are continued coursework and clinical work you will complete. For example, I worked at two different research hospitals providing assessment and treatment for different presenting problems, such as perinatal anxiety/depression, chronic insomnia, and substance use problems. There is also a comprehensive examination, which is a large exam that differs based on the school. Our exam was a written one where we had to complete a systematic review paper on a topic outside our field of expertise.

Completing your pre-doctoral internship

After completing major coursework, clinical practica (experience in counselling centres, hospitals, private practice), and research milestones (defending your thesis proposal), you will apply for a year of full-time supervised work at an internship site. This process is not unlike the residency experience that medical students go throuhg – you apply and get matched as ranked applicants to different internship sites.

The internship is 1 year and is built-in to the doctoral timeline. Altogether, the MA/PhD program with internship is 6 to 7 years on average with the final task typically being defending the doctoral dissertation (though some defend prior to/during internship).

Continued practice and examinations prior to full licensure

As much as I’d like to say that the extensive coursework, clinical work, and research that you have accomplished to this point is sufficient to becoming an autonomous practicing clinician, there’s still a couple more hoops to jump through. The specific requirements to be licensed after the doctoral degree is awarded differs varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Common requirements include passing the EPPP (Examination for Professional Practice in Psychology) exam, which tests foundational knowledge in psychology, and the Jurisprudence Exam, which tests knowledge of ethical practice. Finally, you will also complete 1 year of supervised practice.

Summary

All said and done, the whole timeline to becoming an autonomous practicing clinical psychologist is somewhere around 11 to 13 years after an undergraduate degree, MA/PhD, and post-doctoral licensure.

It’s definitely a long road. But for many who go through it, this career can be extremely rewarding and flexible.

And the experience itself doesn’t have to be miserable; graduate school can be fulfilling and enjoyable depending on your values and specific preferences for lifestyle. For example, I enjoy graduate school because of its flexibility and the different activities (research, clinical work, mentorship, teaching) I get to play a role in on a day to day!

If you found this post helpful, please consider subscribing to the mailing list!

Best wishes,P