-

Examples Of SMART Goals For People With Insomnia

People with insomnia often have a simple goal for their sleep: to sleep better and feel better.

However, what better sleep looks like from person to person can be very different. Some individuals have greater difficulty falling asleep, whereas others might struggle more with waking up in the middle of the night.

Moreover, sometimes people may have somewhat perfectionistic goals when it comes to their sleep.

For example, they might say: “I want to go to bed at 11:00pm, fall asleep immediately, stay asleep throughout the night, and wake up at 7:00am – feeling fully rested the whole day”.

These goals may not be achievable given what we know about sleep. Moreover, some of these goals may actually not be healthy! For example, falling asleep immediately once going to bed may be a sign of excessively sleepiness (which could mean sleep deprivation, or medical problems like sleep apnea).

Below, I discuss some SMART goals that are adaptive and specific to sleep.

SMART Goals for Sleep

Insomnia is defined by difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, and/or waking up too early. People with insomnia also have daytime challenges, such as fatigue, irritability, and difficulty concentrating.

Therefore, goals for insomnia are usually related to these symptoms. Below are a few SMART Goals that are well-calibrated to our knowledge in sleep science to guide your own goal setting.

Goal 1: To fall asleep on average between 10 to 30 minutes.

Generally, good sleepers fall asleep between 10 to 30 minutes most days. An average of below 10 minutes means that a person is excessively sleepy. We also use the word ‘average’ because everyone experiences poor nights – these are common for all sleepers and not a cause for concern (unless it’s happening several times a week).

Goal 2: To generally stay asleep and fall back asleep if awakenings happen

Most people wake up several times over the course of a night. Most are amnestic (people don’t remember) or they last only a few minutes. Therefore, staying asleep completely is not likely; however, most people I’ve worked with are more than happy if they can just get back to sleep rather than tossing and turning for hours on end.

Goal 3: To find the right number of hours and sleep schedule for them

The 8-hour myth is just that – a myth. People vary in their sleep needs and chronotype: that is, how many hours they need to function and when they prefer to go to sleep and wake up.

Therefore, trying to a force an 8-hour schedule when you need less (or more) is counterproductive and can lead to sleep problems. A more helpful goal is to determine the right schedule that will allow for deep, restorative, and consistent sleep to occur (which your insomnia therapist can help with!).

Goal 4: To determine whether improved sleep leads to improved energy, and identify other strategies to reduce fatigue

Many people ascribe their low energy levels to poor sleep. However, the fact is that sleep is only one part of the overall picture.

Fatigue is multifaceted. Many things can bring about fatigue: lack of light exposure, caffeine rebound, too much activity, too little activity, not being hydrated, poor diet – the list goes on.

Therefore, it’s important to be aware of other factors that may be contributing to lack of energy. In my own practice, I often work with clients to understand that the treatment may improve sleep, but we should act like curious scientists about changes in the daytime.

Goals for Sleep Anxiety

One additional aspect of insomnia is anxiety. People with insomnia tend to experience worry about not being able to sleep and the impact of not getting enough sleep.

One additional goal then may be to increase confidence in producing high quality sleep. From a paradoxical lens, our desire to want sleep tends to push sleep further away (kind of like the idea of love is just around the corner when we least expect it).

Therefore, a radical acceptance approach can be very helpful. Radical acceptance means fully accepting the fact that sleep might not come – and that’s okay. Although this thought might seem very scary to some individuals, many of my patients have come to the realization that being awake in the middle of the night is not as dangerous as they thought. In fact, this time becomes seen as a positive experience where they can engage in activities (e.g., watching shows, reading a book) that they typically cannot during the busy-ness of the day.

If you’d like a book to read to learn about science-based strategies when you are in the darkest dark of insomnia, The Insomnia Paradox can be a helpful resource.

Best wishes,

P

-

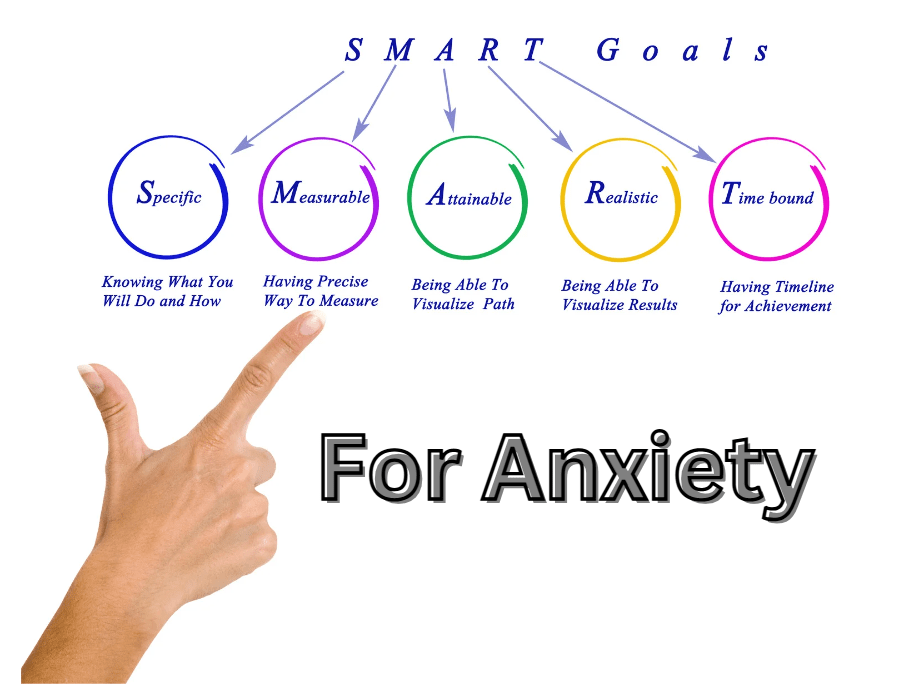

Helpful Examples Of SMART Goals For Anxiety

Anxiety, in its intended form, is often helpful. It helps us to stay safe and prepare in the face of danger. We certainly wouldn’t want to be taking a laissez-faire attitude if a car was racing at us at 100 miles an hour.

At appropriate levels, anxiety is very beneficial. However, when our danger signals become too excessive or persistent, it begins to cause distress and may interfere with our everyday life. For example, a father missing their daughter’s wedding because he was too anxious about getting on a plane. Or a banker forgoing an excellent promotion because she did not want to do a presentation.

Therefore, the goal of treating anxiety isn’t to get rid of it completely. Rather, the goal is to reduce anxiety to the extent that we are able to live the life that we want.

Setting SMART Goals help to create actionable and achievable goals to this end. In this post, I discuss a few possible SMART goals that you can make for different anxiety problems to get your brain flowing on the process!

Examples of different SMART Goals in anxiety

Below are a few different examples on SMART Goals for different anxiety situations. As you will see, they can be quite different in terms of task and difficulty based on where you are in your journey.

Fear of driving

- Driving the car around the neighborhood in the morning twice a week

- Spending 10-minutes sitting in a car and turning it on (but not driving)

- Sitting in the passenger seat while husband drives for 20 minutes

New baby anxiety

- Get husband to give baby a bath without being in the room

- Checking how the baby is doing every 20 minutes instead of every 5 minutes

- Write down three things you are doing well in taking care of the baby every evening

Uncertainty anxiety

- Order food from a new restaurant at least once a week

- Making a phone call to make an appointment without rehearsing what you will say

- Spend 24 hours without checking phone messages or emails

Presentation Anxiety

- Plan to participate at least once in class discussion (asking teacher a question or providing an answer)

- Conduct a 5-minute presentation on a recent school subject in front of parents

Social anxiety

- Smile and say hello to five strangers in a day

- Ask an acquaintance to go to lunch over the weekend

- Talk to at least two people at a party

When it comes to setting SMART goal, the point is to choose something that feels challenging, but manageable. Therefore, put on your creative hat in targeting your anxiety!

Strategies to benefit the most from SMART Goals

When setting up SMART goals, it’s also important to set yourself up for success. Failing a goal can be discouraging and could elicit feelings of guilt.

Sometimes, anxiety can be a barrier to trying to succeed in the goals that you have set. Relaxation exercises, such as guided breathing and meditations, can be very helpful to tune down the anxiety enough to try out these exercises!

After completing the exercise, it can often be useful to reflect on your experience afterwards. Consider what your anxious prediction initially was (e.g., “people won’t smile back if I say hello” or “my husband won’t do a good job and the baby will cry”) and then consider whether that prediction ended up true or not. And even if it was true, reflect on how you were able to cope with the situation.

More often than not, things go pretty well! And even if it doesn’t, you’d be surprised at how resilient you actually are.

Best wishes

P

-

How To Evaluate A Sleep Diary: For CBT Insomnia Therapists

What is a sleep diary?

A sleep diary is a prospective measure that allows people to track their nightly sleep routine. Carney et al. (2012) developed the Consensus Sleep Diary, which is the gold standard measure for sleep tracking.

The sleep diary can be found here.

Each morning, the patient is asked to spend a couple minutes writing down sleep variables from the night before – for example, when they went to bed, when they got out of bed, and how long it took to fall asleep. Typically, patients complete two weeks’ worth of sleep diary to get a reliable and valid index of their sleep pattern.

Information from sleep diaries give CBT insomnia clinicians a good sense of what recommendations to provide to their patients to best improve their sleep. In this article, I provide a general overview of important terms of a sleep diary, ranges of these sleep indices for good sleepers (and poor sleepers), and strategies to improve a patient’s sleep to a normal range.

Important terms to know

Into Bed: Into Bed is the time a patient goes to bed.

Sleep Attempt: Sleep Attempt is the time that the patient tries to initiate sleep. This can be the same time as Into Bed if the person immediately tries to sleep the moment they go to bed. However, some people like to read in bed or do meditation before trying to sleep. In this case, Sleep Attempt begins at a later time compared to Into Bed.

Sleep onset latency (SOL): SOL is the time that people take to fall asleep after Sleep Attempt.

Numbers of awakenings (NWAK): NWAK is the number of awakenings the person has throughout the night.

Wake after sleep onset (WASO): WASO is the total amount of time a person spends awake in the middle of the night. For example, a person could wake up twice in the night, each awakening being 20 minutes each. In this case, NWAK is 2 and WASO would be 40 minutes total.

Terminal wake after sleep onset (Term WASO): Term WASO is the amount lingering in bed after the person wakes up for the last time. For example, if the person wakes up at 7:00am and then spends until 8:00am browsing their phone before getting up, Term WASO would be 1 hour.

Total Sleep Time (TST): TST is the total amount of time a person spends sleeping throughout the night.

Total Wake Time (TWT): TWT is the total amount of time a person spends awake throughout the night.

Time in Bed (TIB): TIB is TWT + TST.

Sleep Efficiency (SE): SE is the proportion of time a person spends sleeping compared to the amount of time they spend in bed (TST / TIB). SE is usually expressed as a percentage; for example, a 50% SE means that a person is asleep only half the time they are in bed.

Bed/Rise Time Variability: These terms refer to how variable a person gets into bed and gets out of bed throughout the week. Less variability means that a person tends to go to bed/get out of bed at a consistent time every day.

Normative ranges on the Sleep Diary

There are general clinical cut-offs insomnia CBT clinicians use to determine whether sleep is closer to the healthy sleeper ranger or the insomnia range.

Good sleepers typically have:

- A sleep efficiency of 85-90% (too low is insomnia range; too high is excessively sleepy)

- A sleep onset latency of 10-30 minutes on average

- A wake after sleep onset of less than 30 minutes

- Bed and rise time variability of less than 1 hour on average

- *The specific number of sleep hours and preference for bedtime/risetime is unique to the person

Evidence-based strategies to improve sleep

As we see from the good sleeper ranges, people with insomnia typically have a sleep efficiency that is significantly below 85 percent. They may also experience difficulties with falling asleep, staying asleep, and/or waking up too early.

There are certain strategies that CBT insomnia clinicians used to break the causes of insomnia.

To put more pressure on the person’s desire to sleep, a sleep restriction protocol can be used. This is typically done by reducing the amount of time a person spends in bed to become more commensurate with how much sleep they are actually producing. For example, if a person is sleeping 7 hours but spending 10 hours in bed, we would ask the person to spend only 7 and a half hours in bed (TST + 30 minutes). A caveat is that we typically do not go below 6 hours for our time in bed prescription.

On the other hand, for people who are excessively sleepy (sleep efficiency > 90%), then we would do a sleep extension and add 15 minutes to the amount of time they are spending in bed.

To regulate our circadian (internal) clock, we typically ask the patient to set an earliest bedtime and latest rise time. For example, setting an alarm for 7:00am every day and getting up at that time.

Finally, to restore an association between the bed and sleeping, we engage in principles of stimulus control. Generally speaking, this means only going to bed when sleepy and getting out of bed if sleep is not coming to do something pleasant instead (e.g., reading a book). More information on stimulus control can be found here.

I hope this post was helpful as a general primer into reading sleep diaries!

Best wishes,

P

-

Behavioural Activation: A Self-Help Guide

Behavioural activation is a type of evidence-based therapy that has good support for its use in improving depressive symptoms (Veale, 2008).

The idea behind behavioural activation is that people with depression are often feeling low and unmotivated to engage with the world. This leads to a loss of positive reinforcement (i.e., things that make people feel good and effective), which in turn leads to even more depressed feelings.

Behavioural activation work to re-add feelings of pleasure and mastery in people’s lives. As the terms suggest, pleasure refers to activities that make us feel good (e.g., spending time with friends, a hot shower) and mastery are activities that make us feel productive (e.g., cleaning our house, learning a language). Some activities give us both!

Some people may have a lot of pleasurable activities in their lives but feel less mastery; other people might spend a lot of time engaging in productive tasks (e.g., work) but have less time for pleasure. Unsurprisingly, having an excess or lack of either (or both) can lead to depressive symptoms.

The article discusses how you can incorporate behavioural activation in your life and improve your mood!

Making a list of activities for pleasure and mastery

The activities that people find enjoyable and productive depends on the person themselves.

Start with making a list of activities that you find pleasure and mastery:

For example:

- Taking a hot shower (pleasure)

- Make the bed (mastery)

- Practice learning a new language (mastery)

- Spending an afternoon lunch with a friend (pleasure)

- Reading a new book (pleasure and mastery)

- Going for a walk (pleasure)

If you’re having a hard time figuring this piece out, think about what activities you used to enjoy or find meaning in. Or if you were feeling better, what kind of things would you want to do. These might be places of inspiration to draw from to get the ideas rolling!

Sorting activities by difficulty

Next, sort these activities by level of difficulty in terms of completing: easy, medium, difficult. For example, taking a hot bath might be an ‘easy’ level task to complete, whereas having a weekend vacation with your partner might be a ‘hard’ level task.

Difficult tasks may be overall more enjoyable or meaningful, but they may not always fit well into a busy schedule or if you’re feeling particularly low. Therefore, starting with easy tasks that give you the biggest bang for your buck can be helpful if motivation is a problem.

Using SMART Goals to set yourself up for success

When we’re setting up activities to include in o our lives, we want to set ourselves up for success! It can feel discouraging to plan to do something but then have it fall through.

Therefore, SMART Goals can be a really helpful to plan activities in a way that support our ability to accomplish them.

For example, an activity you might want to include is taking walks. To make it a SMART Goal, you would specify the when, where, how long, and how often.

- “I will take two walks this week after work for 15 minutes around the neighborhood park”

If you think the goal might be too lofty, you can always amend the goal to make it more likely to complete. For example, only taking one planned walk in the week or reducing the walking time.

Another strategy to troubleshoot is reflecting on possible barriers beforehand.

For example, one barrier might be: “I would feel really tired after work, so I might not go for the walk”. To address this issue, you might decide to go for a walk before work (to avoid feelings of lethargy) or put on your walking shoes 30 minutes before the workday ends to make the transition easier. Be creative with your problem-solving!

Rating feelings before and after trying the activity

Sometimes, our low mood makes negative predictions that we won’t benefit from engaging in these activities.

In these moments, it’s helpful to take on a curious scientist approach and test to see if that belief is true.

Before the activity, write down your current mood rating (1 = very low to 10 = very high) and then write down your prediction on how you will feel after the activity. Once you’re done, engage in the task and reflect on how you ended up feeling! This is a great way to test our beliefs that we sometimes assume is correct.

Summary

That’s it! Feel free to choose activities that work best for you to add a bit more pleasure or mastery into your life. Try to keep an open and creative mind when deciding on activities, how to go about setting yourself up for success, and whether it’s going to be helpful.

If you don’t feel like these will help, remember that sometimes what we do can precede how we feel. I’m sure we’ve all had experiences where we didn’t feel like doing something, but felt a little better afterwards!

Best wishes,P

-

How To Spend The First Session In Therapy As A CBT Therapist

Therapists, especially student clinicians and those at an earlier stage of their career, can often feel disoriented about what the first session of therapy should look like.

In particular, they may experience a lot of pressure to make the session worthwhile for patients and feel compelled to resolve their problems by the end of the session.

Although that outlook is very compassionate to the patient, it’s definitely not the expectation junior clinicians (or any clinician – for that matter) need to have in mind, nor it is necessarily beneficial to the client. Because when we’re in a rush to solve the problem, we might end up losing the patient along the way. Trust and understanding need to be first established before active therapeutic skills should be employed.

The article gives some tips and insights on how you might want to spend the first session in a way that keeps in mind the patient and relieves pressure on yourself to try and cure 20 years of depression in a 60-minute session (spoiler alert: you won’t – and that’s okay!).

Goals for first session

There are a few goals that I like to keep in mind for the first session to best support the well-being of the patient.

First, I briefly introduce myself, go over housekeeping (e.g., consent, limits to confidentiality), and provide some expectations on treatment. This helps the patient to learn more about me and gear the patient towards taking ownership of the treatment. Therapy is not like medication – what you put into it is what you get out of it (i.e., home practice and regular attendance are very important!).

A second goal is to begin establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient. Showing empathy through active listening and statements that accurately reflect the patient’s experience can go a long way to developing positive rapport. The patient will feel heard and consider you as a competent clinician who really understands their problems.

A third related goal is to start learning more about the patient’s presenting problem and obtaining relevant information that is helpful to support developing hypotheses (i.e., case conceptualization). For example, you may start considering how certain thoughts, behaviours, or other patterns might be contributing to the person’s problems. You don’t have to act on it yet, but getting this data will be useful down the road.My last goal is to start working with the patient to develop specific and actionable SMART Goals that they hope to get out of treatment. This process is very collaborative and you should check with the patient to determine if achieving these set goals would make them feel that therapy was a success.

Components of the first session

1. Introductions (2-3 minutes)

2. Housekeeping and expectations (5-10 minutes)

3. Exploration and active listening (20-30 minutes)

4. Sharing CBT model and psychoeducation about the disorder (10-15 minutes)

5. Establish goals (5-10 minutes)

6. Ask for feedback (5 minutes)

I would say if you can touch on most of these components, you are in excellent shape for the first session.

You can see that there are no hints of active therapeutic change (e.g., Socratic questioning or thought records) in the first session because the goal is to really explore and understand the challenges that the patient is coming into therapy with. The first session is a time for building rapport and understanding, and showing that therapy is a safe and collaborative space.

Final Tips

Don’t put too much pressure on yourself! If you go into the session with an open and empathetic mind, genuinely wanting to learn more about the patient, you are going to do just fine.

Remember that both of you bring expertise to the table – the patient is the expert of themselves and you are the expert in treating the psychological problems that they are experiencing.

Therapy is a collaborative space and you should not feel that you have to ‘save’ the patient. Your role is to provide the expertise needed to bring the patient closer to their goals, but the patient must take responsibility and ownership of the therapy as well to truly improve.

Best wishes,

P

-

Stuff You Should Go Through Every Session As A CBT Therapist

Sessions in therapy changes depending on the specific patient and their presenting problem, goals for therapy, and case formulation (hypotheses about what might be the cause of a person’s psychological distress).

Fortunately, a benefit of CBT is that it is very structured. There is a guiding roadmap so that the therapist never loses themselves in the forest of therapy.

This article provides useful elements that are always helpful to touch on in each therapy session even if much of rest can depend on the specific patient’s needs.

1. Setting an agenda

Setting an agenda helps with forming structure during therapy. Of course, many things can come up in therapy and it’s completely okay to deviate at times; however, an agenda helps to get patients back on track if too much time is spent simply talking about a problem (rather than the work needed to get them on track!).

You should also check in with the patient to see how the agenda fits for them and if there is anything specific that they would like to add. This supports a sense of collaboration and creates a feeling of being valued from the patient’s side.

An example of an agenda:

- Check in on the previous week

- Complete mood questionnaires to evaluate progress

- Homework review and troubleshooting

- Introduce behavioural activation

- Assign home practice based on planned activities that bring pleasure and mastery

- Obtain feedback from patient

2. Summarize last session’s main points

Memory is a fickle creature and both the clinician and the patient are liable to forgetting important talking points in the past session.

Therefore, I typically like to briefly mention some of the main takeaways and home practice that was assigned from the previous session. This helps to refresh and consolidate learning, as well as facilitates a smoother transition into the current session.

For example, you might say something like:

“Last week, we had discussed the role those anxious predictions have on your behaviours, such as deciding to stay home and avoid situations. These behaviours relieve anxiety in the short-term but they maintain your problems in the long-term. We had talked about how these behaviours affect areas of your life that are important to you, such as making friends and travelling. To support our goals, we had assigned a home practice to engage in a behavioural experiment to see whether our anxious predictions are actually true”.

3. Obtain a brief update on the past week

It’s also helpful to get a sense of how the patient has been since the last time you spoke to them. This information help guide therapy by understanding how the patient responded to different challenges, emotions, thoughts, and what has been working for them/not working for them.

However, you should be cautious about spending too much time in this area as some patients tend to be more talkative and may get off-track. In this case, a gentle redirection to the agenda would be the proper action.

4. Check in on home practice

Checking in on home practice is necessary to emphasize to the patient the importance of between session homework. Without proper practice of skills, patients will have difficulty seeing improvements and becoming their own therapist.

Therefore, regular check-ins help to set an expectation to patients and gives the clinician a chance to troubleshoot challenges that come up or reinforce successes that they patient might have had.

5. Collaborate on home practice for the following session

Based on goals and topics discussed in the session, there is of course the need to assign specific home practice for the week.

When assigning home practice, ensure that it is collaborative, and the patient understands why they are putting in the hard work for this plan. It’s also good practice to check-in about how they feel about the assigned work and if they are confident that they would be able to properly try it out.

If there are reservations, troubleshoot by asking questions such as “what makes this practice more challenging?” and “how might we make this practice feel for right you?”. The use of SMART Goals setting can be a great way to support the development of achievable and relevant goals.

6. Get patient to summarize main points of the session

To consolidate learning and ensure that the patient has a good sense of the plan for the week, it is often helpful to get the patient to briefly summarize what was discussed during the session.

This is also a good way to check for comprehension and clarify anything that was confusing to them.

7. Elicit feedback from the patient

Although it can feel somewhat vulnerable to ask the patient for feedback, this can be an extremely helpful practice because it really shows to your patients that you care about their well-being.

Moreover, this feedback can be instrumental in making sure that the treatment is going well for the patient and allow for honest conversations about whether changes in therapy are needed. If you’re still a little worried, remember that most feedback will be positive and you’ll typically be seen even more positive light for asking!

-

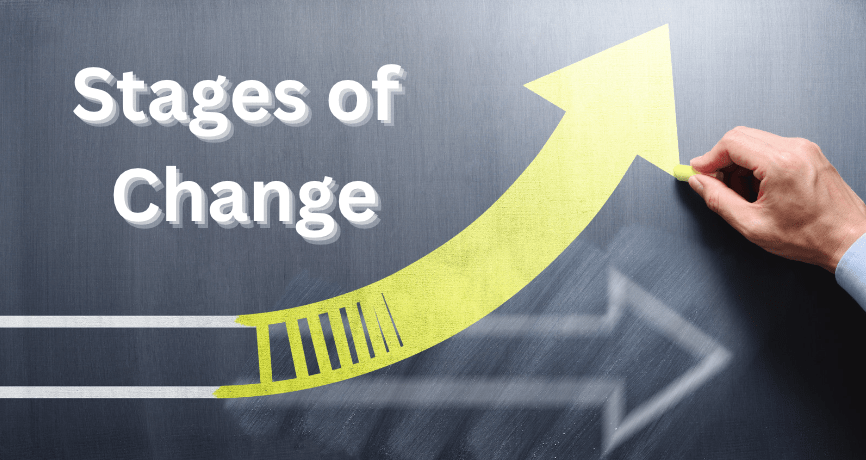

Using Motivational Interviewing To Enhance Patient Commitment To Therapy

Patients come into therapy at varying stages of change. Some patients may be extremely motivated to engage with you and the therapy whereas others may be quite ambivalent about whether therapy is the right course of action.

One example of treatment ambivalence is a person coming into therapy because their family pushed them to reduce their substance use. In these cases, the patient may feel ambivalent about reducing or stopping their substance use because they may not see a huge problem with their use themselves.

We can often see this ambivalence play out in therapy in many interfering ways. For example, patients may skip therapy, not complete their assigned home practice, or not want to collaborate with the therapist.

Therefore, therapeutic intervention is needed to resolve ambivalence or increase motivation to engage in treatment in cases where the patient is not sure if change is a necessity.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a therapeutic skill that works to reduce ambivalence in patients by identifying their values. That is, the therapist helps to determine what is truly important in a patient’s life and determine what actions are most aligned with these values.

Examples of values include:

- Family

- Romantic relationships

- Career

- Health

- Finances

- Activity/lifestyle

- Kindness/compassion/generosity

- Among many others!

In the case above, the patient may come to realize that their substance use is negatively affecting important values in his life: his relationship with his family, his ability to support loved ones financially, and his productivity in his career.

By elucidating these values, the patient is better able to resolve his ambivalence towards making a change and gains a newfound commitment to therapy.

How do we use motivational interviewing?

One simple way to engage in motivational interviewing is by asking a few questions to elicit values from the patient.

Examples include:

- Why is it important for you to make a change?

- What might be some benefits of changing versus not making a change?

- How might life be different if you decided to change?

In some cases, you may want to question about the patient’s life. Through this exploration, you may gain insight into areas that the behaviour in question could be impacting and query about whether these areas are important values.

If you deem it helpful, a more formal pros and cons list can be useful. Patients would have space to write down short and long-term benefits and costs of making a change compared to staying the same. Afterwards, they would consider whether the benefits outweigh the cons and make an informed decision consistent with their values.

Motivational Interviewing does not always lead to greater commitment to therapy

We sometimes think of MI as a way to get a patient to follow through therapy. But that’s not always the case nor should it always be the goal.

All we are doing is exploring a patient’s values and helping them decide what actions are best suited for these values. In a case where a patient realizes that their values don’t really work for therapy, that’s completely okay.

For example, some patients come into therapy for insomnia thinking that they really want to get their sleep back on track. However, they realize that some of the recommendations do not align with their values of having a flexible schedule and following their feeling of sleepiness (CBT for insomnia asks patients to keep to a regular schedule and avoid naps).

In this case, the patient may decide that CBT doesn’t align with their values and realize that they are okay with the consequences of their actions (like napping) because they truly enjoy them. And that’s okay – clinicians should take a very open stance to the patient’s values and not let their own values get in the way of exploration.

Final tips when using Motivational Interviewing

- Motivational interviewing can be used at any time during therapy whenever therapists notice some ambivalence in their patient. It can also be useful to apply a little MI during the initial session, by asking questions like “why have you decided to make a change now?” and “why is it important to make a change?”. These questions elicit responses that help therapists get a good sense of patient values.

- To get a sense of patient’s current level of motivation, it can be helpful to provide information on the different stages of change and give them some examples. You can then query their current stage of change and ask about what makes them more (or less) ambivalent.

- Stay open and flexible your conversations about patient values. It may be possible that your own goals and values are not the same as the patient’s goals and values. This is completely okay! I like to think our job is to simply follow the patient in terms of what is important to them and help align their actions with their values. Sometimes the patient is not quite ready for therapy, and it has nothing to do with you as the therapist. Your patient will also appreciate your flexibility.

Best wishes,

P

-

Determining Your Stage Of Change Before Starting Therapy

Readiness to change model

People come to therapy at different willingness levels to make a change.

For example, a person who needs to get rid of their anxiety about flying in order to attend their best friend’s wedding may be very ready to engage with therapy. On the other hand, a person who must attend mandated therapy because of their substance use may come into therapy not wanting to change at all.

Unsurprisingly, readiness to change affects how much a person wants to work with the therapist and try out the strategies provided.

This article provides useful information to learn about the different stages of change and figure out what stage of change you might be in.

The Stages of Change

There are six primary stages of change:

1. Pre-contemplation

2. Contemplation

3. Preparation

4. Action

5. Maintenance

6. Relapse

The pre-contemplation stage is the first stage on the readiness to change model. This is when the person does not see any issues with their current habits or behaviours and may even see the behaviour as beneficial.

For example, they may find smoking marijuana to be stress-relieving and an enjoyable pastime and do not notice any significant negative effects it has on their life.

People in the pre-contemplation stage are likely not thinking about receiving services.

The contemplation stage occurs when people start second-guessing the usefulness of certain habits. They may start noticing some cons of continuing to engage in behaviour or hear it come up from friends and loved ones.

People in the contemplation stage may start to consider treatments or come into therapy with a fair amount of ambivalence in terms of what they should do.

The preparation stage is the time where individuals become committed to making a change but have not yet employed strategies to tackle their unhelpful behaviours or thoughts.

During this time, they may do research or speak with a therapist on how to best achieve their goals.

The Action stage is the active employment of strategies and learnings to make an improvement in an area of their life. For example, stopping substance use or working towards improving mood.

Once individuals have made a significant improvement, they are now in the maintenance phase. For many people, change is a life-long commitment that requires continual effort to ensure that gains are made.

Finally, it is important to recognize that relapse is very common because change happens throughout our lives over and over again. It is common (and not the person’s fault at all!) if they lose a little progress over the years. When this happen, the individual will re-commit based on their learnings and apply the skills again to get them to where they want to be. In this case, we move from the relapse to the action stage (and back to maintenance).

How do I strengthen my readiness to change?

For some people, they are not sure if a change is needed at this time or if it makes sense to take action at this time.

One strategy that therapists often use is motivational interviewing.

Motivational interviewing is a way for people to carefully consider the pros and cons of making a change based on values. Values are life-concepts that are important to you.

For example, you might ask yourself: “Why is important to make a change?” and “What are the pros and cons of changing compared to staying the same?”.

You may consider the impact that making a change has on values, such as relationships, families, finances, health, personal qualities, among other personal values. You would then make a conscious decision to decide whether it is worth the effort to make a change based on these values.

Afterwards, follow through with a commitment to important values. To support change, there are of course many therapeutic resources that can be helpful to try out!

What if I don’t want to make a change?

That’s okay! It may not be the right time to make a change, or you may realize that the benefits of sticking with your current habits outweigh the cons of making a change. There is no one way to live life and I personally believe you should act in accordance with your personal values.

Best wishes,

P

-

How To Use The Downward Arrow Technique To Improve Mental Health

Carl Jung, a famous thinker in the field of psychology, once said “until we make our unconscious conscious, it will direct our lives and we will call it fate”.

Understanding our inner thoughts and reasons for why we engage in certain behaviours or feel certain emotions is the first step to making a change.

One way to understand our innermost thoughts is through the downward arrow technique.

What is the downward arrow technique?

The downward arrow technique is a common technique used in cognitive behavioural therapy. It can be used for a number of psychological challenges, such as insomnia, depression, and anxiety.

The idea behind the downward arrow technique is that people have different levels of thoughts: 1) surface level thoughts 2) intermediate rules/beliefs and 3) core beliefs. These thoughts can be related to ourselves, others, or the world/future.

Surface level thoughts are those that come up immediately in response to a situation. For example, if a friend cancels a meet-up, the surface thought might be “they don’t want to hang out with me”.

Intermediate level beliefs tend to capture general beliefs or rules that a person implicitly believes. They tend to follow a “if…then…” logic. For example, “if my friends don’t want to hang out with me, then it means I am boring”.

Finally, core beliefs are the very essence of how we think about ourselves, others, the world, and the future. Examples of core beliefs include “I am worthless”, “I am unloveable”, “the world is unfair”.

The downward arrow technique brings us to our core beliefs.

How do we use the downward arrow technique?

Using the downward technique is quite simple. After a situation, you would note down the initial thought that you had in response to the event.

For example, if you’re someone with insomnia, you may have the thought “I’m not going to be able to sleep tonight again” when you’re lying wide awake in bed.

And then you ask the question: “if that were true, then what?”. “Then I would not be able to perform at work.”

“And if that were true, then what?”

“Well, I might be fired from my job”

“And then what?”

“I wouldn’t have enough money to feed my family”

“And then what?”

“I’d be a failure.”

Here, you can see that the pressure of being able to sleep and perform is related to providing for family and worries about being a failure.

Now that I know my core belief, what do I do now?

Once you have identified the different thoughts and beliefs that affect you how you feel, the next step is to tackle them.

Fortunately, there are many strategies that you can apply to work through these thoughts. For example, testing the validity of the thought through thought records or behavioural experiments. Another strategy is to relate to them differently through regular mindfulness practice.

With sufficient experimenting and practice, you’ll start to notice that these thoughts become less automatic and may eventually change your core beliefs. For example, does having bad nights affect your performance as bad as you believe and will you really get fired? You might use a thought record to consider situations where you had a bad night but still manage to get what you needed done.

Best,

P

-

7 Benefits Of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy is a common type of psychological treatment that is useful in treating a number of different psychological problems.

CBT works by changing behaviours and thoughts that maintain a person’s difficulties. For example, tackling negative thoughts in depression or creating exposures for anxiety disorders.

This article discusses seven unique benefits of choosing CBT as your treatment of choice when engaging in therapy.

1. CBT is evidence-based

The bottom line is we know CBT works. Perhaps not for everyone – but as a whole, there is substantial research to suggests that CBT is effective for treating many different psychological challenges and disorders.

For example, CBT has been studied in depression, anxiety, insomnia, anger, chronic pain, psychosis, eating disorders, substance use, among other conditions.

One criticism of the fact that CBT has the most research is because the structure of CBT allows itself to be easily studied. On the other hand, more elusive therapies, such as existential therapy and humanistic therapy, may be harder to manualize and therefore study empirically.

That being said, CBT is definitely an evidence-based treatment that is well-supported by research.

2. CBT is collaborative

When working with your CBT therapist, you should always feel heard and that your opinions and personal goals for treatment matter. You should never feel bulldozed or feel completely directed in how therapy needs to go.

You are the expert in yourself and the therapist has expertise in a treating a specific disorder using a CBT framework. Both are essential in navigating therapy. The collaborative nature of therapy can often feel empowering and validating.

3. CBT is goal-oriented

In the first session, the therapist will work with you to come up with specific goals that you want out of therapy.

For example, you may have specific goals to reduce anxiety or fall asleep quicker in cases of insomnia.

Based on these goals, the therapist will help you develop SMART goals (specific and measurable smaller goals) to get you to your end journey. The therapist will also help to tackle barriers that may come up along the way.

One clear benefit of having specific goals is that it allows the therapy to not get side-tracked and both you and the therapist have a clear idea in what you are working towards.

4. CBT is actionable

There’s a saying in CBT that “what you put into it is what you get out of it”.

Therapy doesn’t exist within a vacuum in a 45 minute session in a therapist office. Oftentimes, patients are asked to practice the skills they have learned to work on tackling thoughts or changing behaviours to break out of a vicious cycle that contributes to their problems.

Therefore, therapists will provide patients with relevant and useful strategies that patients can use to work on their challenges. It’s like having a toolkit with a bunch of different therapeutic skills that you can pull from to best handle things that come up.

5. CBT is individualized

Although many CBT treatments are manualized, there is significant room for flexibility based on the needs of the patient.

There is a concept called case formulation, which is a fancy term when therapists are gathering information and making hypotheses about what could be causing difficulties in a patient‘s life and maintaining their problem.

Through this formulation, decisions can be made about what recommendations could be most effective. Of course, hypotheses can change as more data comes up, so the therapist will be flexible when something isn’t working.

6. CBT is structured

As discussed, the structured format of CBT (e.g., setting an agenda, providing education, homework planning, etc.) helps to ensure that there is always a roadmap in treatment.

This structured approach can be anxiety-relieving for patients who prefer having a plan. If interested, here’s a post on how the first session might go in CBT therapy!

7. CBT is time-limited

Finally, CBT is time-limited: most treatments start with the end in mind and the therapist and patient decide on a specific number of sessions for therapy.

A time-limited approach can be helpful in ensuring that sessions stay on course and productive. Moreover, the skills-oriented and time-limited approach lets patients work towards becoming their own therapist.

By becoming their own therapist, patients do not have to rely on their therapist as a crutch and can manage challenges that come up in the future!